The Reading Habit for Senior School Students

The Reading Habit for Senior School Students

My parents filled my childhood with books. Before the arrival of acne and armpit hair, I had devoured hundreds of books, both fiction and non-fiction. I especially loved funny books and football books. I read a lot. And then, around the age of 14, quite suddenly, I stopped reading books altogether. If I was reading at all for the next few years, it was mostly music magazines. At times, I tried novels I knew clever people were supposed to read - Orwell, Kafka, Austen - but did not enjoy them and could not get through them. I did not even finish all the set texts I had to read for English Literature. I found literary analysis difficult, artificial, even painful. A-Level put me off Dickens, Joyce and Shakespeare: I understood that they were ‘Great’, but I did not enjoy reading them. I did not go back to reading novels for pleasure until I was at university, when it was a great way to avoid doing the required reading for my course.

I am not alone. A 2019 survey in the UK found that only 50% of 11-14-year-olds and 41% of 14-16-year-olds say they enjoy reading, compared with 72% of 9-11-year-olds. Boys report significantly less enjoyment of reading than girls in the teenage years. The curriculum at our school becomes more rigid and demanding after Year 9, and this is when our students stop having timetabled library sessions. Reading (except for texts assigned by teachers) is relegated to something optional - encouraged, but to be done in free time. We all know that there are more distractions for children nowadays, with mobile phones and social media, not to mention streaming TV and ever more dazzling video games. Finding time to read is more difficult than ever. How do we switch our children (back) on to reading?

Why is reading for pleasure important?

Research has shown that reading for pleasure correlates not just with improved academic performance across many subjects, but also with reduced stress levels and improved wellbeing. Even a short time spent reading every day can help. But let's not see reading for pleasure as another compulsory school activity that must be suffered through. It is impossible to force somebody to enjoy something, but we can provide the environment for enjoyment to happen. Contrary to some beliefs, reading fun or escapist books does not rot children's brains or hold back their development.

The brain undergoes major changes throughout adolescence and into adulthood, often causing emotional turmoil as young people figure out how to deal with other people and find their place in the world. Teenagers can sometimes feel that adults don't understand them, no matter how many times we insist that we went through it too. Fiction can speak to teens clearly and powerfully when a parent or teacher is struggling to connect.

One great superpower of fiction is the magic: how far away we can get from our own reality. Particularly in these times, when the news is mostly negative, our lives have contracted, and the outside world seems a long way away, it is an amazing thing to have another reality to escape into, even if only for twenty minutes in the evening. Our mental state can receive a boost from taking time out with fiction.

What should our teenagers be reading?

The boom in fiction aimed at teenagers over the last two decades has resulted in an enormous increase in high-quality books for our children to read: the best of them are on a par with the best writing for adults. For young readers, the contexts and characters in these books are more relatable, and the settings more familiar, than in adult fiction, so it's easier to inhabit that world. But that doesn't mean they are all lightweight or escapist. Authors have pushed the "young adult" (YA) boundaries to write serious and complex stories that openly acknowledge teenagers' feelings, embrace diversity, and empower the reader to not just understand but change the world. The success of The Hunger Games, over a decade ago, spawned a whole genre of "young adult dystopia" which is still going strong. It does not take a scholar to work out why stories in which the world has gone horribly wrong (thanks to the selfishness or inaction of the grown-ups) and the teenagers must sort everything out, might be popular with today's young people.

Reading fiction has always been partly about empathy. If we see other lives, feelings, points of view in stories, we can start to understand other people who are very different from us. Although in the US and UK the publishing industry is still overwhelmingly a middle-class, white business, diversity in YA is improving, thanks to a loose coalition of authors leading a move towards increasing the variety and quality of portrayals of gender, race and sexuality in fiction aimed at teens. There is now a greater chance that young readers can see themselves reflected in a major book character, whether it's the way they look, sound, or feel deep inside. Because of this range and quality of YA fiction, I believe we shouldn't force Great Literature on young people before they are ready - that could instead be a recipe for killing enjoyment. I would argue that it is just as important for today's international teenagers to read Angie Thomas and Patrick Ness, Jason Reynolds and Elizabeth Acevedo, as the mid-twentieth-century classics such as Harper Lee and J.D. Salinger, or Lord of the Flies and The Outsiders. Who knows whether these books will end up as "classics" in fifty years? However, for now, this thriving literary scene is the place for young readers to be.

Does it have to be fiction?

Many teenagers, just like many adults, have little patience for fiction but love finding out about things, whether it be science or sport, music or clothes, politics or computer games. This should certainly not be less valuable than an appreciation of fiction. Reading non-fiction is extremely valuable: it helps us understand the world and communicate, in a time when untruths and manipulation are all around. There are more and more superb non-fiction books aimed at young readers these days, in different formats. Some are written as narratives and therefore help to nurture reading skills in a similar way to reading a novel. But whatever your child is reading, even if it is "only" articles on the internet or in a magazine, every little bit helps. And if your child really struggles to pay attention to long texts, there are other ways to engage with stories too: well-plotted TV series or films; drama at school; podcasts and audiobooks; news articles on a topic of interest; even an immersive video game can have a complex story. It may sound a bit childish, but if we continue to talk to our children about these stories all around them, we can show that we value stories and can learn from them.

Of course we all want to get our teenagers reading more. However, it did not do me any lasting damage to miss out on a few years of novel-reading. A teenage drop-off in reading was normal then and it is normal now (I still like funny books and football books, and a lot more besides.).

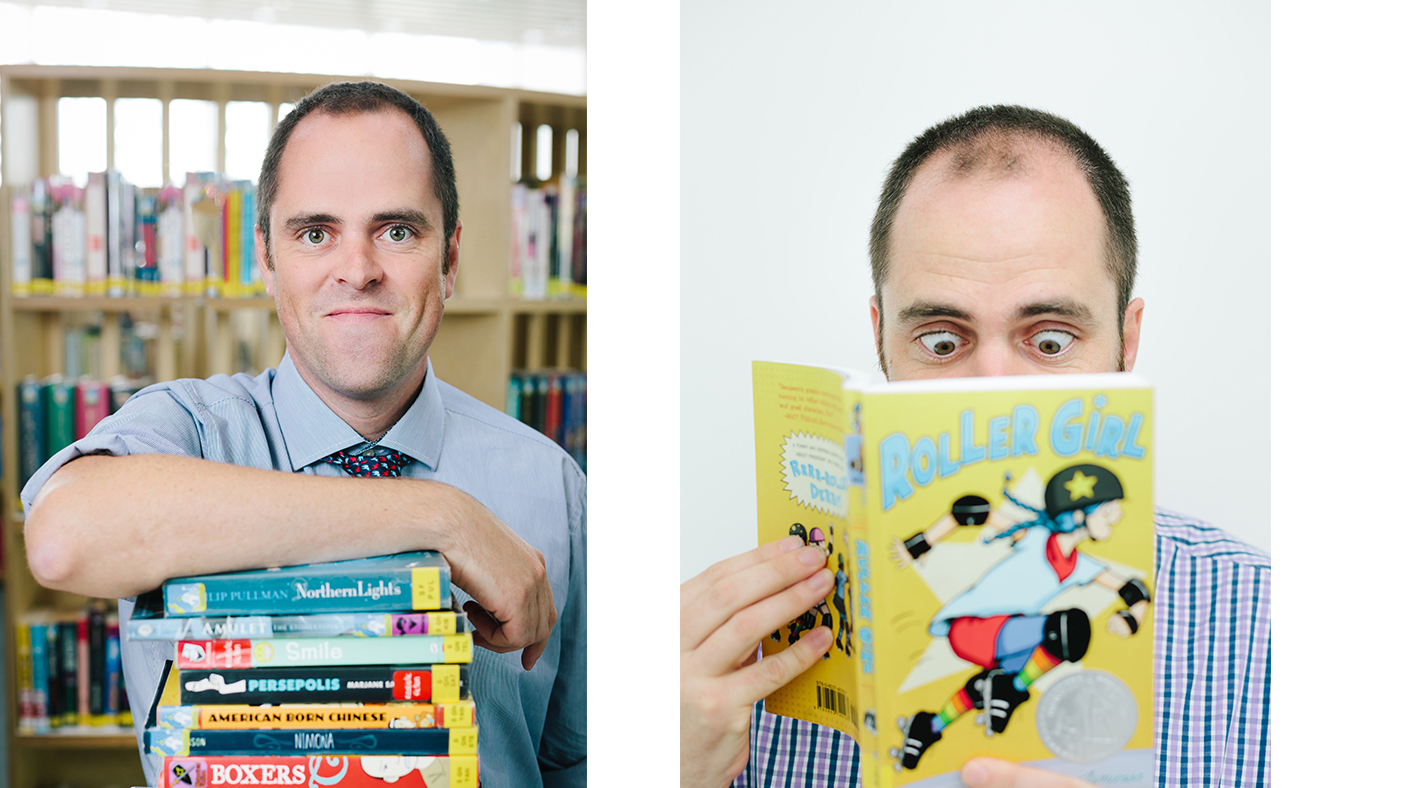

Mr Tim Appleton

Senior School Librarian